The pitch always starts the same way.

"Our engineers can build this with a small team in one year."

It sounds reasonable. You've done harder things.

One year later, you're usually still building. Or the project has quietly died, and nobody wants to talk about it. Or you'reback on the phone with us.

We interviewed 15+ large experimenting organizations, including current customers, former customers, returning customers, and non-customers.

All had built or seriously considered building an internal tool.

The builds didn't fail because the code was bad. They failed because the organization couldn't sustain them.

Every role became a single point of failure. Pull out one card, and the whole thing collapses.

Here’s the 100 Million dollar question: Should you build or buy an experimentation platform?

TL;DR

- Internal experimentation platforms fail for organizational reasons, not technical ones.

- Every role becomes a single point of failure: product owner, strategist, lead developer, data scientist.

- Budget cuts hit experimentation first. It's seen as a luxury until it's gone.

This is what keeps a program standing...

Build what's core to your product. Buy everything else.

We follow this at Optimizely. Despite being a technology company, we have hundreds of technology vendors.

Experimentation feels like it should be core. It touches your product. Your engineers want to build it. But for most companies, experimentation is infrastructure that enables product work.

A lot of times, experimentation is seen as a luxury. When budget cuts come, it's early on the list.

The internal platform team gets reduced. Maintenance slips. Features stall. The program build that was supposed to save money becomes an underfunded liability.

Why your house of cards collapses

Every role becomes a single point of failure. This is what makes in-house experimentation a house of cards. Pull one person out, and the structure collapses.

Image source: Optimizely

Image source: Optimizely

1. Product owner

Experimentation programs live or die by executive support. Everything depends on having a product owner who believes in testing and will fight for it internally.

Teams end up focusing on tests that require heavy buy-in from product leadership. Political dynamics take over. The product owner becomes the person defending the program's existence, not just running it.

When this card falls: Loss of a champion means loss of program support, which means loss of the program.

2. Experiment manager

Someone has to own documentation, iteration processes, and institutional knowledge. This usually falls to an experiment manager or strategist.

Programs constantly change how they maintain hypotheses and learning libraries. Teams rarely connect hypothesis libraries with learnings in any durable way. Knowledge transfers rarely happen.

When annual reviews come around, and macro KPIs have moved less than 1%, stakeholder enthusiasm disappears. The strategist can't point to a clear record of what was learned and why it mattered.

When this card falls: No one can explain what the program learned or why it mattered. Stakeholders lose faith.

3. Developers

Coding for experimentation is specialized work. Developers get stretched across experimentation tooling and regular product work. Burnout from dual responsibilities. When the lead developer leaves, the entire program can crumble.

Keeping up with the ever-changing web environment and evolving experiment practices requires bandwidth that internal teams rarely protect.

When this card falls: The lead developer leaves, and the entire program crumbles with them.

4. Data scientists

Statistical rigor requires specialists who stay current. Keeping up with changing statistical models requires dedicated people. Data scientists and stakeholders argue over methodology and interpretation. The rise of AI adds new complexity around hallucinating results.

When this card falls: Methodology gets questioned, results lose credibility, and the program loses its foundation for decision-making.

5. QA

Most companies don't have dedicated QA for experimentation. The existing QA team is already underwater with their regular workload.

Experimentation adds a significant testing burden. Inadequate resources to properly validate experiments.

When this card falls: Bad experiments ship. Trust in the program erodes.

6. Designers

Most companies don't have dedicated designers for experimentation either.

Companies are stingy with designer allocation generally. Even less willing to dedicate designers solely to experimentation. Design becomes a huge bottleneck for test velocity.

When this card falls: Test velocity grinds to a halt, waiting on design resources.

Why do companies convince themselves to build?

If it's a house of cards, why do smart companies keep trying?

Here’s why:

1. We can't let customer data leave our walls

Companies want complete control over customer data and analytics. So, you're forced to build your own analytics warehouse. The third-party tools get reduced to traffic splits while everything else moves internal.

This concern is valid. But you can solve it without building an entire experimentation platform from scratch.

2. The vendor costs too much

Once the costs of a third-party platform rise above a certain level, organizations believe they can save money by building internally.

The decision to build rarely includes robust cost modeling. Requirements gathering is incomplete. Because the idea starts with engineers, non-engineering needs get underestimated.

We've built a cost model that includes inputs from organizations considering internal builds. Every time, the result is the same. Internal platforms cost more to get less.

Optimizely has had hundreds of engineers building our experimentation platform for over fifteen years. A small team can't close that gap.

3. We've built harder things

The pitch always sounds reasonable. A small team. A couple of years. We've done harder things.

But experimentation programs require diverse, committed teams. The build estimate covers the code. It doesn't cover the organization you need to run it.

4. If Amazon can do it, so can we

A small group of companies with market caps over $250 billion, unique engineering cultures, and thousands of engineers have built good internal tools. When someone from those companies joins a smaller organization, they assume the playbook transfers. It usually doesn't.

The in-house experimentation platform struggles to achieve intended cost, velocity, and capability goals.

5. Experimentation velocity

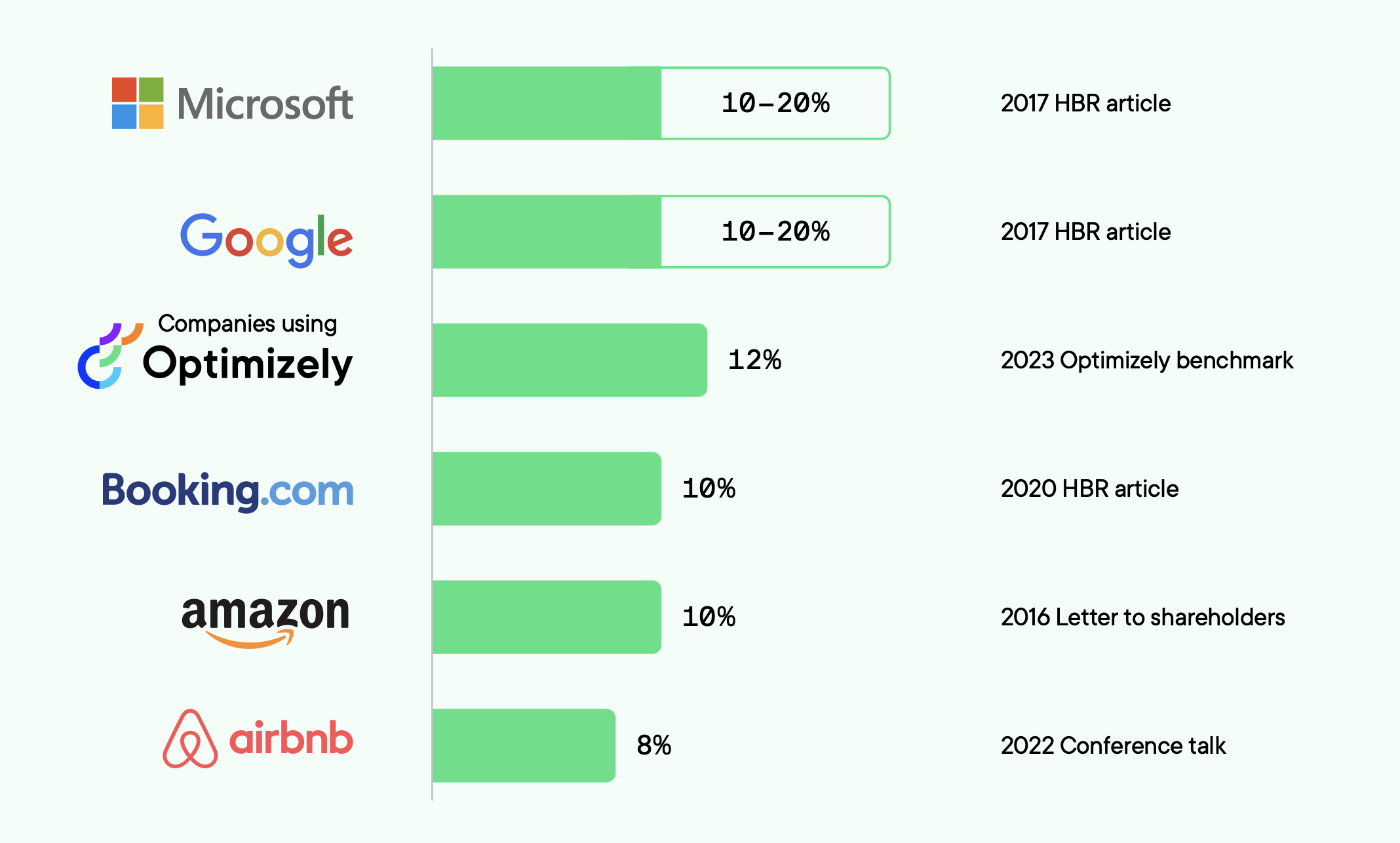

It is a factor of quality and velocity. We’ll set experiment quality aside for the purpose of this exercise and assume that all the experiments being run are the ‘right ones’ to run. You need velocity because what experimentation exposes is that even the smartest companies can only guess the best digital experience 10-20% of the time.

If you are only going to get 1-2 out of 10 bets right, you need to make a lot of bets!

We consistently find that even with existing in-house tools at $100B+ companies that the velocity is a lot lower than what it could be with Optimizely.

6. Give us a year

Ideal team size for a mature experimentation program: 10-20+ specialists.

Engineers. Data scientists. Experiment managers. Strategists. Designers. QA. Someone whose job is stakeholder advocacy.

Most internal builds start with a few engineers and a mandate to figure it out.

How does this play over time?

Time-to-value keeps slipping...

Internal builds are rarely fully scoped. Time-to-value extends beyond everyone's expectations. Twelve months become thirty. Resources get reallocated before the platform reaches the functionality that was promised.

You end up with a half-built tool that a shrinking team is expected to maintain.

When building makes sense

While buying is often the best choice, there are scenarios where building an in-house experimentation platform could be justified:

- You are Amazon: There is a very small number of companies with market caps north of $250B, high technical expertise, and unique cultures that had experimentation so deeply in their DNA from day 1 that they invested the right amount, at the right time to build a good internal platform and actually have some credible competitive advantages because of it.

- Existential data risk + scrutiny: For that small number of companies in that $250B+ market cap bracket, especially with previous data-related breaches, scandals, or government investigations, it may be worth it to be able to say that no 3rd party ever has access to any 1st party data.

- Hybrid approaches: Some of our customers want to build some components of the experimentation platform and buy others. The circumstances are too diverse to capture broad trends, but this can be a mid-point option.

What causes the velocity drop?

Even when the cards stay standing, the structure is shaky.

-

No interface and UX

They underestimate the time and efficiency costs of an easy-to-use interface for all parties, including engineers.

- New engineers can’t figure out how to run experiments so it’s harder for experimentation to scale.

- Stakeholders who may do a lot of the planning work like marketers or product managers can do no work related to experimentation. Many small, non-technical tasks must be done repetitively by engineers.

-

Experiment run time

Separate from the quality of the statistical algorithm, because the program is a black box, even the act of checking on an experiment is a large lift. If that large lift is performed, it may result in the finding that the test hasn’t reached significance, which means a task that is already expensive to perform just once, has now been done multiple times per experiment. Some internal systems ‘solve’ this problem by setting pre-determined test run times, but this is wasteful in many use cases if the test reaches statistical significance early.

-

Data analysis

Even simple test analysis requires multiple, cross-platform steps by analysts. In the Optimizely platform it takes 5 minutes to look at our results page.

Image source: Optimizely -

Data accuracy

Consistently randomizing audience groups and then maintaining consistent bucketing across visits or platforms is hard to do. We’ve had multiple large customers who left us to build their own platform only to return a few years later because they ran 100+ A/A tests and could never deliver credible results. Nobody wants to run tests when they don’t trust the data!

-

Governance + Visibility

Because these systems are often black boxes only alterable by engineers, there is a higher likelihood for erroneous deployments or broken variations to stay live for longer. When something goes wrong, because nobody can see what’s going on, it’s harder to diagnose and the platform and discipline lose credibility in the organization quickly.

-

Documentation

Any technology requires lots of documentation to enable more teams. Keeping those documents up to date is an incredible amount of work that they don’t have time to do.

How to make the right decision

The buy vs. build debate isn't one-size-fits-all. To start, conduct a thorough analysis. Perform a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis, factoring in not just initial development costs but also ongoing maintenance, opportunity costs, and potential limitations.

For reference, Optimizely commissioned Forrester Consulting to conduct a Total Economic Impact™ (TEI) study and demonstrate the potential financial impact of adopting Optimizely. What more, you ask?

- Assess core competencies: Ask yourself whether building an experimentation platform aligns with your company's primary focus and competitive advantages. But how do you go about finding the right platform for your needs? Our experimentation RFP template shows the questions you should be asking.

- Consider long-term implications: Think beyond immediate needs and evaluate how your choice will impact scalability, flexibility, and resource allocation in the years to come. For example, your experiments, need to reach statistical significance. Optimizely's sample size calculator ensures you no longer need to wait for a pre-set sample size to ensure the validity of your results.

- Seek expert advice: Consult with experienced practitioners and vendors in the field. If you have a platform or are thinking of building one, come to us! We’ll do a buy vs. build total-cost-of-ownership and velocity evaluation for you.

We will run the numbers with you (for free)

Get the real math before you build. We offer a total cost of ownership study. We'll model your situation and show you the real numbers.

If you're an Optimizely customer and someone in your organization is pushing to build internally, reach out to your Customer Success Manager.

If you're not an Optimizely customer but have a platform or are considering building one, same offer. Have a conversation with us for a build vs. buy evaluation.

No cost, no strings. Our advice is informed by hundreds of customers and fifteen years in the business, and you can do whatever you want with it.

- Last modified: 2/27/2026 1:25:06 PM